Heroines for the Planet: Author Susan Freinkel Digs Up Plastic’s Secret History

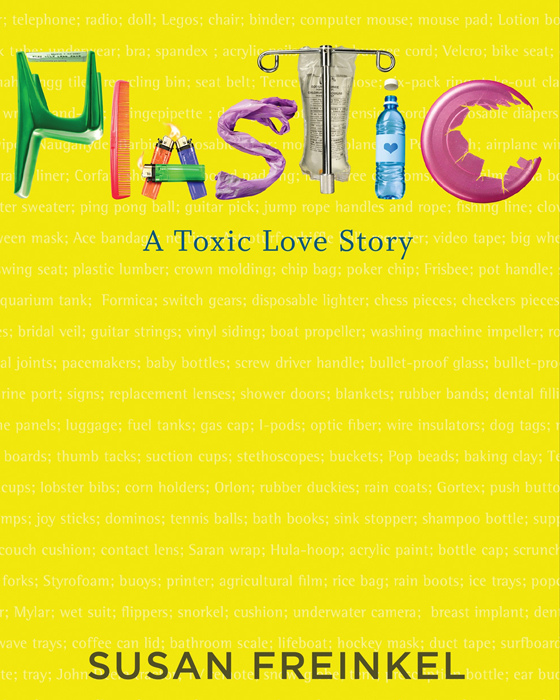

Have a look around you. Chances are you’re surrounded by plastic — the subject of San Francisco science writer Susan Freinkel’s new book, “Plastic: A Toxic Love Story.”

We love to hate plastic, and yet, we can’t seem to live without the stuff. For better, but too often for worse, plastic has invaded and influenced nearly every aspect of our lives. Susan cleverly explains this complex love affair with plastic in a page-turner that will surely have you veering off your plastic-paved path.

I asked the busy author and mother of three about plastic’s history, its grave dangers to our health and the environment’s, and what we can each do to better our relationship with plastic.

Lindsay: What inspired you to write Plastic: A Toxic Love Story?

Susan: Living in San Francisco, I was watching the debate about plastic bags unfold, and it started me thinking about plastic. I thought I would try to go a day without touching anything plastic. But the absurdity of that idea became clear first thing that morning when I walked into the bathroom and confronted my plastic toilet seat. So I decided instead to spend the day writing down all the plastic I touched. And by day’s end, I was staggered by the length of that list. My life, I realized, was really permeated by plastic – and not just predictable things like plastic bags. But unexpected items, like my “brass” doorknob or “chrome” tub faucet, or even the omnipresent little stickers on my organic fruit. I realized I didn’t really have any idea what plastic was, how it had become such a ubiquitous part of modern life, or the extent to which its ubiquity was really a problem. Those questions seemed good fodder for a book.

Lindsay: Plastic is now perceived as very harmful to the environment, but it was first created to help preserve natural resources and animals, is that right?

Susan: That was a surprise to discover. One of the first plastics, celluloid, was invented in response to widespread fears about an impending ivory shortage. Ivory was used for a number of things, including billiard balls, and the game had become so popular people feared elephants were being hunted into extinction. A billiard manufacturer offered $10,000 to anyone who could develop a viable substitute. And that ad inspired a New York inventor who eventually came up with celluloid. Among its many virtues was that celluloid could be made to mimic ivory, as well as tortoiseshell – also taken from an endangered species — coral, ebony, and other scarce and precious natural materials.

Lindsay: Plastic built the modern world in many ways, and it’s engrained into our daily lives in nearly every way imaginable. How did humans become so dependent on plastic?

Susan: It was a combination of industry narrowing the choices available, and the seductive appeal of many plastic applications. Take for instance, the plastic shopping bag. That was the product of a deliberate push in the late 1970s by the polyethylene manufacturers to find a new outlet for that plastic. By then the industry had already successfully replaced paper for sandwich bags, dry cleaning bags, garbage can liners, and produce bags and was actively looking for new outlets for polyethylene. Shopping bags were a logical next stop. But at first, shoppers and grocers and didn’t much care for them: the bags flopped over, didn’t look they could hold as much as paper sacks. Clerks had to lick their fingers to pry a plastic bag loose. So, incredibly enough, the industry sent out trainers to stores around the country to teach grocers and shoppers how to use the bags. Within about six years plastic had mostly replaced paper at the checkout stand. And now we’ve gotten very used to the convenience these bags offer. They’re lightweight. They’re waterproof. We get them for free every time we shop. And we don’t want to give them up. That ambivalence is one reason the plastics industry has managed so successfully to fight proposals to ban or restrict the bags.

Lindsay: Why is our relationship with plastic so complicated? In some ways, plastics have been good for us. What went wrong here?

Susan: It’s complicated because plastics do offer many great benefits, sometimes even alongside the problems they impose. The classic example is in modern medicine, which wouldn’t exist if not for plastics – from prosaic stuff like Band-Aids and disposable syringes to cutting-edge digital imaging devices. But unfortunately, some of the plastic devices that are vital to life saving treatments also may leach chemicals that are hormone and endocrine disrupters and which may have long-term impacts on human health. The other way in which the relationship went wrong was through the increasing use of plastics for single-use conveniences. Half of all plastic produced goes into single-use items, many of which, like the plastic bag or drinking straw or pizza protectors, are little more than pre-fab litter.

Lindsay: In your book, you tell plastic’s history through eight very familiar objects to us all: the comb, chair, Frisbee, IV bag, disposable lighter, grocery bag, soda bottle and credit card. Why did you choose these objects?

Susan: I decided to tell the story through objects because that is the way we encounter plastic – not as some abstraction, but in the things that pass through our hands in our everyday lives. I knew there were certain themes that I wanted to explore in telling plastic’s story, so I was looking for objects that would allow me to delve into those themes. For instance, I knew I wanted to talk about the place of plastic in design, and how it offered a new kind of artistic freedom to designers, as well as a new medium for schlock. I wasn’t sure what object to use until I stumbled across a website devoted to plastic patio chairs – those cheap, tacky chairs that are found all over the world — and learned that technologically speaking, the chairs were descended from efforts by the great designers of the mid-twentieth century to create beautiful plastic chairs.

Lindsay: While writing and researching the book, did you come across a statistic that you found particularly jaw-dropping?

Susan: One of the most shocking statistics to me was that we have produced nearly as much plastic in the first ten years of the 21st century as in the entire previous century. It says to me that we are becoming ever more dependent on plastic, especially single-use products, and increasingly exporting that reliance to the developing world – which is where the fastest growing markets for plastics exist today. It suggests to me that we are reaching a tipping point, underscoring the need for us to start finding solutions for the problems associated with plastic.

Lindsay: I was startled to learn that all Americans now carry traces of dozens of synthetic chemicals in our bodies. Can you expand on this jarring fact?

Susan: That fact reflects the degree to which synthetic chemicals pervade modern life – present in our clothes, furniture, food, packaging, toys, tools, soaps, cosmetics and so on. We are exposed daily to a barrage of chemicals – and due to the laxness of chemical laws in this country, many have not been adequately vetted for safety. And yet while the presence of trace levels in our blood or urine is a jarring fact, the health implications are not clear-cut, in part because in most cases the levels are extremely low, and in part because many of these chemicals work in more complicated ways than classic toxins. Many of them are endocrine disrupters that interfere with the network of glands that orchestrate growth and development and/or that interfere with natural hormones. As such, they may have their most significant impact on a person who is exposed during critical windows of development –in the womb, as a young infant, a toddler or a young teen.

What’s more, the effects may not show up for years or even decades. That makes it difficult to draw straight lines between cause and effect. There is, however, evidence from animal studies and epidemiological studies to suggest some of these chemicals may indeed pose health risks. For instance, I looked at a chemical called DEHP, a type of phthalate, which is a chemical added to vinyl to make it soft and flexible. DEHP suppresses testosterone; animal studies show high doses are toxic to the male reproductive system, and some epidemiological studies show an association between exposure to DEHP and sperm quality and fertility, as well as thyroid function and liver toxicity. But not all the dots have been fully connected.

The bottom line is that we are all living in a giant uncontrolled experiment on chemical exposure. That’s why I believe we need tougher laws governing the chemicals that are put into commerce – ones that would require manufacturers to demonstrate the chemicals they want to use are safe for human health and the environment.

Lindsay: What can eco-chick.com readers do to change their relationship with plastics, aside from pick up a copy of your book?

Susan: Unlike many troubled relationships, this is one that can be bettered without a lot of pain:

1. Refuse single-use freebies: Bring your own bag when shopping. Carry a travel mug for your daily caffeine fix. Tell your waiter you don’t need a straw.

2. Reuse where possible: Give that sandwich baggie a week’s workout; use that empty yogurt tub for leftovers.

3. Quit the bottled water habit. You can stay just as hydrated with a reusable bottle made of stainless steel, aluminum, or BPA-free plastic.

4. Learn what you can recycle. Find out what plastics your community recycler accepts. Explore other recycling resources: UPS stores will take back shipping peanuts; many grocery chains will take used bags and plastic film; many office supply chains will take back used printer cartridges.

5. Don’t cook in plastic. Heat can cause hazardous chemicals to leach out of some polymers, so transfer food to glass before microwaving.

6. Support efforts for change. Support companies and businesses that are making the effort to reduce excess packaging and to use more recyclable materials. Support legislation aimed at restricting or banning single-use products like shopping bags. Tell your elected representatives you want tougher chemical laws.

7. Push for your state to pass a bottle bill – a law that has shoppers pay a small deposit when they buy a beverage, which is refunded when the bottle/can is returned. States with bottle bills have far high recycling rates, as well as lower litter rates.

Lindsay: What does our future relationship with plastic look like? Is it too early to tell?

Susan: We’re certainly not going to eliminate plastic, but I am hopeful we can find ways to produce and use it more wisely. There’s great interest right now in making “greener,” plastics, using renewable sources like plants, rather than fossil fuels, for the feedstocks. That holds great promise for a new generation of plastics that would be biodegradable, compostable and non-toxic. But only if they are manufactured to be biodegradable, compostable and non-toxic – so we need to push for industry to fulfill that promise!

Lindsay: Susan, many thanks for this enlightening interview.