Fracking in New York State: Artists, Mark Ruffalo, and Thinking About Water in NYC and Beyond

A piece by Winn Rea on display at St. John the Divine

On the eve of World Water Day, several hundred people gathered at sunset in one of the world’s largest Catholic cathedrals to bear witness to the most crucial environmental issue of our time- the misuse and fragility of the world’s clean drinking water. Amy Goodman, the leading lady at Democracy Now!, opened the event, raising a glass to “the world’s finest champagne, not bottled.”

For the past six months, the cavernous cathedral at St. John the Divine has been showing dozens of artists’ works, such as Mark Rothko, William Kentridge and Jenny Holzer in the exhibition ‘The Value of Water”. The varied work spans mediums but the thread of water ties them together. What does this mean for the art presented?

In one piece a series of bottles filled with water from different holy sites in Israel sat illuminated in a case, and in another, long plastic curly-ques hung from the ceiling appearing like bubbles rising to the surface of an ocean; up close the bubbles reveal themselves to be plastic water bottles.

The next day marked the 19th anniversary of World Water Day. I opened my Twitterfeed to see what was being passed around on the topic across the internet. With an issue so wide, there was a never ending flow of staggering statistics, Top Ten lists of how to limit consumption, anecdotes of its misuse, and stories of shortages from developing nations across the world. As I spun through the blips I wondered what the impact would be on the average citizen reading these tweets and articles. Would they take shorter showers for a few days? Finally buy a reusable water bottle? There are so many small ways to limit our uses of water, and these do add up (and make us feel better about ourselves in the meantime), but much greater issues plague the planet’s fresh water, and reversing the crisis lies in bigger hands than our own.

One of these hands is the natural gas industry, which has been expanding in the past decade using a new method of drilling termed hydraulic fracturing (coined fracking by the industry). In order to be able to fracture the bedrock beneath the earth, massive amounts of water mixed with carcinogenic chemicals such as arsenic, benzene, methanol and nearly 750 other compounds are shot into the ground to break apart the rock and release the natural gas, which is then captured and used in our stove-tops, in our buses and other energy intensive activities.

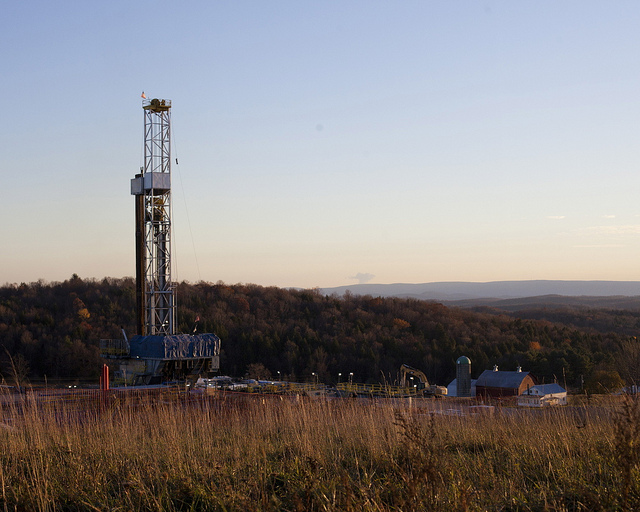

A fracking site in Susquehanna County, PA. Photo by Mark Ovaska

There are so many reasons why this new form of energy extraction is terrifying and a handful of reasons why politicians are heralding it as our new ‘clean’ energy source, but let’s start with the bad news. Aside from the sheer amount of water required to blast apart bedrock (millions of gallons per well), there have been cases of gas wells leaking into nearby water wells.

The small town of Dimock, Pennsylvania rose to fame after poorly made gas wells leaked and contaminated a handful of the town’s water wells, which now sput out foggy methane-polluted water, and can literally be lit on fire. Just imagine for a second, if you were able to run your faucet in your kitchen, light a match and watch a flame appear where water flows. Sounds like something from a sci-fi movie, am I right? If you’re not familiar with the concept, I would recommend the Oscar nominated documentary Gasland, which was one of the main exposers of the perils of fracking to an unaware country.

New York City, home to 8 million water-guzzling people, prides itself on having some of the best quality water on earth, and I’m faithful that I can turn on the tap and not be harmed by what’s coming out of it. The area of proposed fracking in New York lies dangerously close to the reservoirs that provide water to the city. After Dimock’s water became contaminated, the NY-based group Water Defense, founded by Oscar-nominee Mark Ruffalo, began transporting NYC tap water to residents of Dimock after the company responsible for the contamination refused to do so. Who would be able to provide for the Big Apple in the case that our reservoirs become polluted?

I keep going back to the lines of the brilliant poet Samuel Coleridge in his poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner;

“water, water everywhere, but not a drop to drink.”

At this point the famous line is trite, but the sentiment burns more than ever before.

Back at the cathedral, I was staring up at a pair of Fredericka Foster prints of placid, blue water, hanging next to a pair of gothic columns and beside an oil painting of the Last Supper. The photographs, embodying simplicity and peacefulness, seemed appropriately placed in such an important setting.

Water is holy, in however way you’d like to define the word. We can continue to each do our small part to curb the water crisis, but with an issue like fracking, its eventual abolishment is only possible by citizens like yourself taking a stand for protecting the ‘world’s finest champagne’.