On Nature Blindness (Mine and Yours)

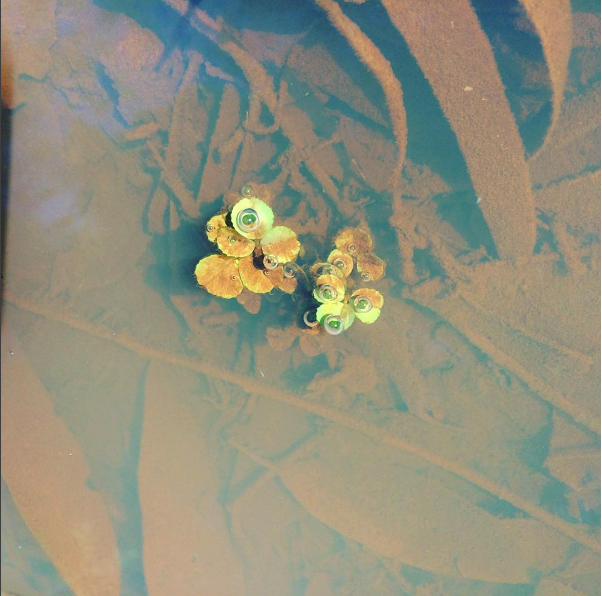

Last night I laced up my sneakers and headed for the hills—the Fire Trails of the Berkeley Hills, specifically, which criss-cross the forested and be-fielded rises and arroyos of this East Bay city. These are steep hills, as they tend to be out west, and my heart pumped hard within minutes as walked up, up, up for almost 15 minutes before it flattened out (near where the image above was taken). I noticed the intense green of the grassy, exposed areas, and the myriad tiny plants that have sprung up since we’ve had a month of rain. It’s more Pacific Northwestern here than I’ve ever seen it before, and I love it.

There’s a curve in the trail where I run, which is huddled with eucalyptus, redwood, cedar and other trees that compete for light by going vertical; one of my favorite things about the western forests is how tall the trees are and how small a human can feel running beneath them. Compared to the eastern forests of my youth, they are consistently impressive.

The height of even 100-year-old second-growth forest here is a small joy—and gets me thinking about my European ancestors. In my case these people wandered the old-growth tall-tree landscapes of Germany and Armenia (that country is now almost entirely deforested, though amazing groups like the Armenia Tree Project are working to restore them). My Scottish and English ancestors once wondered through miles of thick-trunked trees, though probably even further back in time: check out the video below about ancient landscapes and how they have been transformed by human endeavor, but have left clues of their once-aliveness behind.

So I delight in these trails, and even as I share them with plenty of other runners (from students to hearty older folks with dogs), they feel like they are my own. At one of the curves, there are a pair of Great Horned Owls who regularly hoot-hoot to each other in what could only be described as mournful tones at dusk, which is my favorite time of any day. I stop my run when I hear them, which is usually, and as I wait for my heartbeat to settle, I try to find their feathered bodies high among the eucalyptus trees. (There are groups of people here that argue that the 100-year-old-plus trees in this grove, since they aren’t native species, should be removed. Tell that to the owls, who live in them without discrimination.)

Once a young woman stopped and craned her neck alongside mine up towards the treetops: She said, “What have you found?” and I pointed to the one owl. His feathery eyebrows were perfectly silhouetted against the sky, his body as one shadow with the tree branch below. Her smile was wide when she spotted it, and she listened for awhile as the owls hooted back and forth. She thanked me and continued on her run, but I stayed and listened for awhile, and was rewarded with a great flapping of wings and a silent glide above the path, where I was treated to a sweet silhouette of an owl being an owl.

Each time run at that blue hour, I hear the owls, whose voices carry in that particular spot quite well (I assume this is one of the reasons they have chosen it), I stop. It always takes several minutes to make them out. They are shadowy, and it’s dusk, and they are 60 feet up. Unlike my cat, or the owls, or almost any wild animal, I’m used to looking at things that are easy to see. The human world is a simplified one, with bright colors, un-subtle shapes, and straight edges. It is, generally, ugly. Or at least it seems so to me, whenever I return to it from spending time outside.

I noticed this first as a child, when I would come inside after hours in the woods. I’d track after deer, pull up rocks to see what was underneath (worms when it was wet, pill bugs and/or ants in the summer and fall, larvae in the spring), “decorate” my forts with rocks in various shades, watch birds forage for seeds, craft boats from skunk cabbage, and mud-bathe, just as if I were in a tub, in the deeply rot-musky wetlands. If you look at anything in nature, it is almost endlessly complex—just stare up at any old tree canopy and it has hundreds of levels of light an color; look at any wetland and there’s so much going on it takes days to even start to understand it all.

My time outdoors as a child gave me what I uncreatively call “nature eyes”—something I think all humans once possessed. Of course, some of us still do, and many have much better ones than me—any natural scientist, from geologists to birders have nature eyes with great specificity, and guides in every rainforest I’ve been lucky enough to visit (Costa Rica, Mexico, Australia) see at least 100 times what I can. They are reading the landscape as surely as I read a newspaper, parsing meaning, remembering what came before, tying ideas together.

In the new book “How to Read the Water” the explorer and natural navigator Tristan Gooley passes along much of his knowledge about how the watery part of the world works. He starts with what can be gleaned from the smallest puddle in a muddy dirt lane, and details how native Pacific Islanders navigated the vast ocean via a deep understanding of tides, how water acts around land masses, seasonal winds, and other clues available to anyone who is interested and paying attention. I appreciate his insistence that this is not mysticism, it’s accessible information. Gooley writes:

Once we know the things to look for and what these influence, every patch of water we see is beautiful, fascinating, and a clue to something else. We learn to see the water as part of an intricate network, a matrix if you like. At various times these skills have been called magic, and more recently, psychic—they are neither. They are the fruits of a little curiosity, awareness, and a willingness to join the dots.

Gooley’s book was a bestseller, which means that many of us are starving for this information about the world we live in and are surrounded by. But so many others don’t even know what they are missing. And if you can’t even see something, it can’t really exist as a reality to you. That’s how humans are—seeing is believing.

Many are missing these basic connections: When I taught ecology to 6th and 7th graders from NYC one summer in the northwestern corner of Massachusetts, I went over the required science curriculum, but first I had to give them a crash course on seeing and hearing in the woods. Most of them didn’t know where to put their feet to cross a stream, and couldn’t judge how muddy mud was by looking at it, and ended up a mess, confused as to how they were ankle deep in the earth. A natural meadow was just a field of green. I had to get them down on hands and knees and tell them to look for 10 different plants before they even noticed they existed as separate flora. I did the same with a rock covered in lichen and moss. And the bark of the trees. Finally, the students started to recover their sight; it wasn’t just green stuff on a rock, but colonies of 7, 8, 9 different mosses and lichens. It wasn’t just a field of grass, but an ecosystem with a variety of plant life. And then they noticed the insects, which were completely invisible before.

They just couldn’t see them.

I have done similar exercises with adults; even those who grew up outside cities. This blindness is more common than nature eyes, at least in my experience.

So scientists and environmental advocates can go on about natural wonders, and what if people just don’t know what they are talking about? When we discuss global warming’s implications, it must feel very far away to most, for whom sea-level rise is an abstract concept. For whom those flying things are all just “birds” and so who cares about diversity in the chickadee or wren populations? If you don’t know the difference, then all you are seeing is birds around, as they always have been. If you don’t know their songs, they all sound the same. And this is the danger of our blindness—not just that we miss out on the richness of life on earth, which is sad, but that we don’t even notice when change is happening before us. And that’s not just sad, it’s dangerous.

I have it too. I recognize some of what Gooley points out in his book for example, but plenty of it is totally new to me. I am missing all kind of information due to my own ignorance, things I would just know if I had lived 100 years ago or 1,000 years ago and grew my own food.

I don’t even know all the things I don’t know. My nature blindness, is, I hope, just a bit of myopia, but I could be legally blind. I have no idea.

The more modern we get, the more simple and streamlined we seem to like our visual world; the complications and nuances of the natural world are gone, replaced by the smooth, the predictable, the unchanging. And so we all become more blind, and things disappear, and we can’t see their absence because we didn’t perceive their presence.

Maybe nature eyes is a curse of sorts—I can see what we are losing, and its heartbreaking.

All images by Starre Vartan.